THE RAINFOREST IS DISAPPEARING!

A CRY FOR HELP

A REQUEST FOR HELP

Biodiversity as a Genetic Bank

For centuries, the rainforest has been a haven of untouched nature, the ultimate expression of life and the most splendid adornment of our planet.

It has represented a treasure of biodiversity beyond all expectations, hosting over 70% of all animal and plant species.

The indigenous people of the forest have always revered it, using it wisely and sustainably.

Over the past 50 years, population growth, increasing land demand, the pursuit of quick profits, and technologies that allow the felling of centuries-old trees in minutes and the clearing of any type of land have led to the destruction of half of the existing tropical forests. In the 1980s and 1990s, the deforestation rate even doubled. Every minute, an area of tropical forest equivalent to eight soccer fields is destroyed worldwide.

WHAT THEY ARE

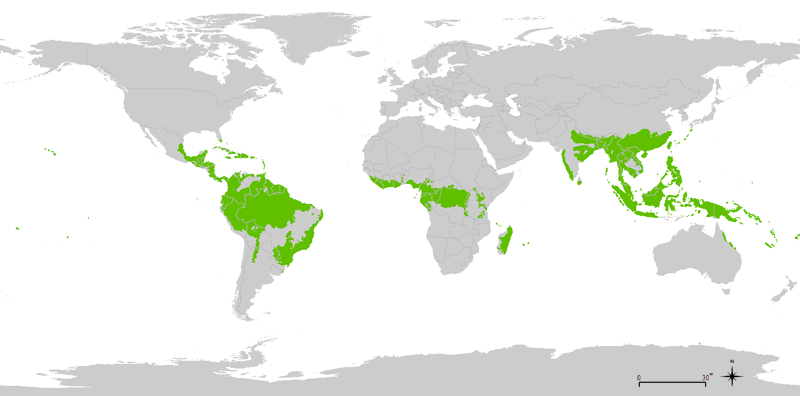

Tropical forests, covering a mere 6% of the Earth’s surface—about 1.2 billion hectares—host over 70% of the planet’s species, making them immensely valuable. Despite this, they face significant threats. Often referred to as rainforests, although they can experience dry spells, these ecosystems were characterized in 1898 by a German botanist as having constant humidity and rainfall of at least 2000 mm annually. Located between the equator and 10° latitude north and south, these areas are marked by heavy rainfall, high humidity, and warm temperatures. The environment of tropical forests is shaped by climate and soil type, influencing which species can flourish. Altitude further divides these forests into lowland and montane categories. Lowland forests, like those in the Amazon basin, are vast yet endangered by logging due to their accessibility. These rich ecosystems boast canopies over 45 meters, with emergent trees reaching up to 60 meters. The tallest recorded tree was 83 meters. Valued for their timber, these trees are a key resource. Lowland subtypes include mangrove forests, thriving in salty, muddy coastal waters, and floodplain forests along waterways, which are periodically flooded, such as the igapó in the Amazon. Montane rainforests feature shorter trees due to cooler climates, inconsistent rainfall, and limited nutrients. These forests are essential for environmental protection, preventing soil erosion, and mitigating flood impacts with their sponge-like properties. Tropical forests, influenced by climate, altitude, and rainfall, vary widely. Costa Rica, for example, despite its small size of 51,000 km², contains 12 distinct forest habitats.

THE MAIN TYPES OF FORESTS

1) DRY TROPICAL OR DECIDUOUS FOREST: rainfall between 800 and 2100 mm, temperatures above 24° C, lowland forest; two main vegetation layers. The first, about 30 meters high, forms a natural canopy under which extends a second layer, 5 to 10 meters high. During the dry season, most trees shed their leaves, focusing energy on fruit and seed production. Butterflies, bees, and bats play a crucial role as pollinators and also aid in seed dispersal. This is the most threatened forest type in Costa Rica, with only 7% of its original territory remaining. To protect what’s left, the government has established the Santa Rosa, Palo Verde, and Barra Honda national parks.

TROPICAL HUMID AND TRANSITIONAL FOREST (humid forest): Characterized by substantial rainfall of 3,000 to 4,000 mm and temperatures exceeding 24°C, this forest type is found below 1,200 meters in elevation. It features a diverse blend of deciduous and evergreen plants, with a canopy height of over 35 meters. The forest contains multiple vegetation layers and hosts 50 to more than 100 tree species per hectare, with dominant species being particularly rare. It is the most prevalent forest type in Costa Rica, primarily located in the Nicoya Peninsula and Guanacaste.

TROPICAL RAIN FOREST: Temperatures range from 18 to 24°C, with rainfall reaching up to 8000 mm. These forests are primarily found in lowland and hilly regions like the Amazon, with altitudes reaching up to 1200 m, including montane rainforests. The climate is consistently stable year-round, supporting evergreen and moisture-loving plants that create complex layers in the undergrowth. Canopies can soar to heights of 45-55 m. In Costa Rica, these forests are predominantly located in Corcovado.

Explore the National Geographic Education article

CLOUD FOREST: Situated at altitudes above 1500 meters, this ecosystem experiences temperatures ranging from 6 to 12°C. Perpetually enveloped in mist, it is formed as rising air expands, cools, and nears the dew point. The vegetation here is lush, dense, and evergreen, with limited stratification. Tree trunks are adorned with mosses, lichens, orchids, and some epiphytic bromeliads. Tree canopies tend to be narrower and rounded, with thick, short, and twisted branches. This forest spans the slopes of the central-southern mountain range and volcanoes, serving as the birthplace of many significant rivers. To safeguard this vital habitat, Costa Rica has designated Rincon de la Vieja, Braulio Carrillo, Chirripó, Amistad, and Poas as national parks.

WHY THEY MATTER

Tropical forests, often called the Earth’s lungs, are crucial oxygen producers, alongside marine plankton. Through photosynthesis, tree leaves transform solar energy and carbon dioxide into sugars and cellulose. Beyond oxygen generation, plants absorb carbon dioxide, a harmful byproduct of burning coal, gas, and oil in industries, vehicles, and heating systems. Currently, industrial emissions release about 5 billion tons of CO2 into the atmosphere annually, with tropical forest fires contributing 2 billion tons. These fires burned 16 million km of forest last year alone. The rising CO2 levels form a shield that traps solar heat, leading to a greenhouse effect, raising Earth’s temperature, and causing climate changes. These changes threaten to melt ice caps, raise sea levels, and expand deserts. Unlike temperate forests, tropical ones operate year-round, absorbing more CO2 and helping mitigate the greenhouse effect. However, rampant deforestation in these regions poses a threat to global climate systems, potentially impacting daily life. In Modena, for instance, CO2 emissions rose by 7% from 1990 to 1996, with gasoline consumption up by 30%, and subsequent data show even more troubling trends. Tropical rainforests are also vital for water, with rainfall reaching up to 8,000 mm annually. Trees absorb rainwater and release it into the atmosphere, forming clouds that return as rain. Acting like sponges, they hold and gradually release water, serving as crucial reservoirs. Deforestation disrupts this cycle, causing soil erosion and reduced rainfall, leading to diminished vegetation. The climatic effects extend far beyond the tropics, where forests influence weather patterns, cooling tropical regions while warming more extreme latitudes.

THE BIODIVERSITY OF TROPICAL FORESTS

Biodiversity encompasses the rich variety of life across all its forms, levels, and combinations. From trees and flowers to insects and birds, every living organism reflects genetic diversity within Earth’s diverse environments and ecosystems. Tropical forests are particularly renowned for their unparalleled biodiversity, housing over 70% of the world’s animal and plant species. In Europe, a hundred-hectare plot might support 25 to 30 tree species, whereas an equivalent area in tropical forests can sustain as many as 400 species. This diversity extends to animal life as well, evident in the contrast between the species found in Costa Rica and Italy.

Understanding the richness of species in tropical forests is complex, influenced by numerous factors that create ideal conditions and intricate, delicate relationships. A key factor is the abundant solar energy, perfect for growth, paired with nutrient-poor soil. This imbalance encourages the evolution of species adapted to exploit the limited ecological niches available. Furthermore, the towering, layered structure of trees provides shelter for many smaller plants, like climbers and epiphytes. These diverse plants offer a wide array of food resources and hiding spots for various small animals.

The lack of a winter season, which typically interrupts the life cycle of insects, has enabled a smooth diversification, fostering selective pressures, competition, and intricate forms of symbiosis and mutualism. Some biologists suggest that insect pressure has spurred plant diversification, compelling them to evolve new defenses. Despite the vast number of species, individual numbers per species are often limited, and their distribution is confined. Consequently, deforestation not only devastates forests but also leads to the extinction of numerous animal species, many of which might remain undiscovered.

Rainforests are fascinating for their intricate web of interrelationships among countless species. Take, for example, a bromeliad that collects water; it engages with pollinating and seed-dispersing insects, the tree it inhabits, and the animals that rely on its water reserves. While some of these interactions are reciprocal, others are not. Central relationships often spawn additional dependencies, such as those between ants and ant plants, or figs and fig wasps, termed “keystone mutualisms.” Environmentalists are increasingly worried about rainforest fragmentation, as losing a key species can upset this fragile equilibrium.

BIODIVERSITY AS A GENETIC BANK

Many global crops are now monocultures, with minimal genetic diversity. Farmers have selected varieties that are highly productive, easy to harvest, and flavorful, resulting in plants that are nearly identical. Currently, eight crop types account for 75% of the world’s food supply. This genetic uniformity leaves us highly susceptible to pests, crop diseases, and climate change. Should new diseases or pests emerge, these monocultures could face devastating impacts, as resistant plants have been excluded from cultivation. Wild plant species may be vital for adapting current varieties to changing conditions. Deforestation not only leads to species extinction but also erodes the genetic diversity needed for plants to adapt.

Tropical forests are not just havens for biodiversity; they are also crucial sources of medicinal resources. Many essential drugs are derived from plants found in these lush ecosystems. From shrubs, flowers, seeds, roots, and fungi, these forests yield medications such as anesthetics, antibiotics, contraceptives, and treatments for heart disease, malaria, and other conditions. For example, the antimalarial drug quinine is extracted from the bark of various Cinchona species, native to the Andes. The Rauwolfia plant from Asia and Africa provides reserpine, a treatment for hypertension and mental illnesses. Additionally, legumes like the Australian Moreton Bay chestnut (Castanospermum australe) produce castanospermine, which holds promise in the fight against AIDS.

Approximately three billion people rely on traditional medicines, mostly derived from plants, to treat illnesses. In India and China, 80-90% of these traditional remedies are plant-based, with China utilizing around 5,000 different species. Globally, forests serve as the richest reservoirs of medicinal plants. In Kenya, for instance, 40% of plant-based treatments originate from forest trees. Forest inhabitants, who act as custodians of an extensive natural pharmacy, could significantly aid in the discovery of new medicinal plants. Without forests, many of these valuable medicines might remain undiscovered. In the Amazon, an ethnobotanical team has documented over 1,000 plant species utilized by indigenous communities, mainly for medicinal purposes.

For indigenous communities in tropical forests, biodiversity is vital for more than just aesthetic, medicinal, and genetic reasons; it is crucial for their cultural survival. Unfortunately, these communities often face dire circumstances: they lack legal ownership of the lands they inhabit, and the forests they depend on are being destroyed. It is distressing to see the disappearance or assimilation of ethnic groups who have lived in harmony with nature, pressured by values they cannot embrace. Protecting tropical forests by establishing new reserves, with indigenous people as guardians and managers, not only preserves biodiversity but also safeguards these invaluable cultures from which we have much to learn.

WHAT THREATENS HER

Tropical forests, abundant in resources, are found in some of the world’s poorest regions, which are grappling with increasing overpopulation. Nations in these areas are seeking to enhance their quality of life through development that heavily relies on the intensive use of natural resources, primarily from forests, and industrialization modeled after Western practices. As a result, these forests are expected to face heightened pressures in the coming years. With half of these forests already destroyed and an additional 30% at risk of vanishing in the next two to three decades, the outlook is alarming. Industrialized countries, including ours, share the responsibility by driving demand for tropical timber and supporting livestock markets that graze on once-forested lands. Further complicating the situation, rising international debt between rich and developing countries often compels forest-rich nations to overexploit their resources.

The Impact of Agriculture

Deforestation has unfolded without regulation or planning, driven mainly by settlers in search of arable land. They have cleared, burned, and exploited vast tracts of untouched forests for agriculture, leading to severe environmental harm. The primary driver of tropical forest destruction is logging for agricultural purposes, with large areas being cleared to create farmland. Farmers often resort to clearing forest plots to cultivate subsistence crops. Practices like “slash-and-burn” are frequently the only option due to nutrient-poor soil, yet they are rarely sustainable. The ecosystem suffers permanent damage, forcing settlers to abandon the land after a few years and move elsewhere to repeat the cycle of destruction. Some of this land is used for growing export crops like tea and coffee for wealthier nations. The true culprits behind this destructive path are poverty, overpopulation, and unequal land distribution, leaving settlers with few alternatives.

Timber Extraction

In tropical regions, timber plays a crucial role as a major source of foreign income. The annual revenue from timber trade surpasses $10 billion, with the production of about 30 million cubic meters of raw logs. Large tropical trees continue to be felled to supply high-quality wood for export to affluent countries, where demand is steadily increasing. Locally, only around half of the various species are utilized, with a limited number being in demand internationally. Unfortunately, even selective logging inflicts severe damage on the forest. The felling of a single tree can cause others nearby to collapse, and the heavy machinery used for transportation disrupts soil and vegetation. Roads constructed by traders to access cutting areas and transport logs are later used by farmers, who further intrude into the forest, exacerbating the damage. This leads to irreversible ecological imbalances. It’s not merely a tree that perishes; entire ecological niches vanish.

The Breeding

Livestock farming, often marking the final phase of forest degradation, has been a significant catalyst for environmental harm. Over the past thirty years, cattle farming for meat production has severely threatened the tropical forests of Latin America. In Central America and Brazil, widespread deforestation has been encouraged by government incentives such as tax breaks and World Bank subsidies, aimed at producing inexpensive beef for local consumption and export to North American and European fast-food markets. Within just two decades, over a quarter of Central America’s tropical forests have been cleared to make way for livestock farming. However, this practice frequently becomes unsustainable within a decade, as decreasing soil fertility forces ranchers to move to new areas. This unsustainable model is underscored in the “hamburger connection” report.

Mining Activities

In many tropical countries, forests offer more than just timber and agricultural land; they conceal vast mineral wealth and hold rivers with significant potential for generating renewable hydroelectric power. While deforestation from extractive activities isn’t the primary threat to rainforests, the roads and infrastructure developed for mining often lure settlers seeking new land. The Amazon Basin is abundant in mineral and oil resources, similar to regions in New Guinea, the Philippines, and Indonesia. Among the most ambitious mining initiatives is Brazil’s Grande Carajas Program, a $70 billion investment spanning an area of the eastern Amazon as large as France. Central to this program are vast iron ore deposits beneath the forest. Eighteen pig iron foundries are planned, with the first in Maraba, Para operational since March 1988, utilizing charcoal from the untouched rainforest. Once all plants are active, approximately 2,300 square kilometers of virgin forest will be destroyed yearly for charcoal production. Additional industrial pressures on tropical forests include oil drilling and illegal gold mining by landless farmers. In Mindanao, southern Philippines, Costa Rica, and areas of the Amazon, gold rushes have polluted rivers with mercury—a byproduct of gold extraction—and disrupted tribal communities. In Brazil, thousands of gold prospectors, or garimpeiros, have established open-pit mines in the Amazon, felling trees and excavating large pits, while mining waste continues to contaminate rivers.

HAMBURGER CONNECTION

At first glance, linking fast food burgers to tropical deforestation and the extinction of numerous species may seem difficult. Yet, the “hamburger connection” illustrates how Western individuals can inadvertently contribute to tropical destruction from afar. The United States, with a significant appetite for hamburgers, imports 33% of the global beef market to cater to less than 1/20 of the world’s population. Much of this “low-cost” meat comes from Panama, Costa Rica, Guatemala, and other Central and Latin American countries, ultimately landing between buns and ketchup in the U.S. In these regions, forests are cleared for cattle farming. In 1980, 72% of Amazon deforestation in Brazil was attributed to creating pastures for livestock. Similarly, the European Economic Community imports meat from tropical America and Africa. While the monetary costs for the U.S. and EEC are minimal, the global energy, environmental, and social costs are vast, and the ecological damage is irreversible. Producing meat for a single hamburger in a tropical area requires a space equivalent to a 12-square-meter living room. In this space, cleared to produce roughly 100 grams of ground meat, over 500 kilograms of living matter, including plants, flowers, butterflies, birds, and monkeys, once thrived. This results in enormous energy waste, requiring centuries for recovery. A primary tropical forest’s regeneration can span anywhere from 600 to 1,000 years. In this context, Western consumers can help mitigate the issue by reducing meat consumption imported from these countries, while Western governments can play a significant role by implementing regulations and economic policies that respect tropical ecosystems.

SOME FACTS ABOUT FORESTS

Half of the forest has been decimated from its original expanse, predominantly in the last thirty years.

Only 12% of the world’s forests remain in their pristine, untouched state; the rest have been modified in various ways due to human activity.

1% – The portion of forest destroyed each year due to ongoing deforestation processes

3 – The nations of Russia, Canada, and Brazil hold the world record for virgin forests, hosting a total of 70% of these pristine areas. These countries are key to global environmental conservation due to the vast expanse of primitive forests found in their territories..

85 – There are nations in the world that have completely lost their original primary forests

Around 400 million individuals globally rely on tropical rainforests for daily sustenance. These forests supply crucial resources, including food, water, and materials for building and crafts, while also providing a natural setting that upholds their cultural traditions and ways of life.

Tropical rainforests cover six percent of our planet, serving as a keystone for global ecosystem health. These vibrant forests are home to a stunning array of biodiversity and are integral in climate regulation and oxygen production, functioning as the Earth’s green lungs. Preserving these forests is crucial for sustaining environmental balance and the survival of innumerable species.

Approximately half of the world’s living species, encompassing both animals and plants, inhabit tropical rainforests. These ecosystems, rich in biodiversity, host a vast array of organisms, many of which are unique to these environments.

Around 20% of the world’s bird and plant species have evolved from the Amazon basin. This region is a hotspot of biodiversity, teeming with a vast array of unique species that have developed over millions of years. The Amazon offers a complex and varied habitat, nurturing the rise of remarkable biological diversity.

Twenty-five percent of pharmaceuticals globally are sourced from plant species, with 70% of these coming from rainforests.

A remarkable 99% of rainforest plants remain unexplored and unexamined for pharmacological purposes. This astonishing statistic underscores the vast potential these plants possess, with many likely housing unique and valuable chemical compounds ideal for developing new medications. Our current understanding barely scratches the surface of what awaits discovery in these rich and diverse ecosystems.

A University of Idaho report reveals astonishing statistics.

How much would it cost to artificially replicate the free benefits that forests naturally provide?

A University of Idaho report reveals impressive statistics.

| Function | Cost in Nature | Cost for the Man in Euros |

| Water purification | 0 | 0,62/liter |

| Air purification | 0 | 0,04/liter |

| Climate moderation | 0 | 19.600/day |

| Wind protection | 0 | 5.200/hectare |

| Wild genes | 0 | 9.800/gene |

| Tourism | 0 | 1.800.000/parc |

| Flood control | 0 | 21.200/hectare |

A TREE: 50 YEARS WELL SPENT

| Oxygen production | € 27.300 |

| Reducing air pollution | € 54.200 |

| Erosion control | € 27.300 |

| Recycling of harmful substances | € 32.500 |

| Total Euro | € 141.300 |